As organizations scale, roles naturally become more complex. What begins as a flexible startup structure eventually turns into overlapping responsibilities, inconsistent titles, and unclear career paths. Without a structured system, compensation decisions become reactive, promotions feel subjective, and workforce planning grows harder to manage.

This is where job architecture comes in.

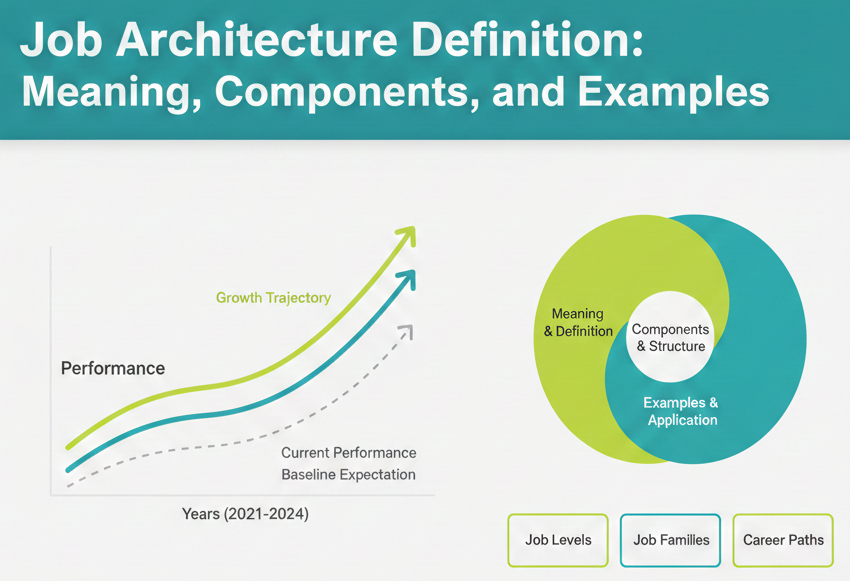

Job architecture provides a structured framework that defines how roles are organized across the company. It establishes clear job families, levels, responsibilities, and career progression paths. More importantly, it connects role design to compensation strategy, performance expectations, and long-term workforce planning.

For HR leaders, job architecture improves internal equity and career transparency. For finance teams, it brings predictability to compensation planning and headcount forecasting. For employees, it creates clarity around growth and advancement.

In this guide, we’ll break down:

- The definition and meaning of job architecture

- Its core components

- Different models companies use

- Practical examples of job architecture frameworks

- How to build and implement one effectively

1. What is Job Architecture?

Job architecture is a structured framework that organizes roles within a company based on function, level, scope, and impact. It defines how jobs relate to one another and establishes clear pathways for progression, compensation, and accountability.

At its core, job architecture answers three fundamental questions:

- How are roles grouped across the organization?

- How is seniority defined and differentiated?

- How does progression translate into scope, responsibility, and pay?

A well-designed job architecture creates consistency across departments. It ensures that a “Senior Manager” in one function reflects a comparable level of complexity, impact, and accountability as a similarly titled role elsewhere in the organization.

Job Architecture vs. Job Descriptions

A job description explains the responsibilities of a specific role.

Job architecture defines how that role fits within a broader structure.

While job descriptions are tactical and role-specific, job architecture is strategic and organization-wide.

Job Architecture vs. Org Charts

An organizational chart shows reporting relationships.

Job architecture defines role hierarchy and leveling standards — regardless of reporting lines.

For example, two employees may report to different managers but still belong to the same job family and level within the architecture.

Job Architecture vs. Career Frameworks

Career frameworks focus on growth pathways and skill development.

Job architecture provides the structural foundation that enables those pathways. Without architecture, career progression lacks consistency and fairness.

2. Why Job Architecture Is Important

Job architecture is more than an HR exercise. It is a foundational system that influences compensation fairness, workforce planning, and long-term organizational scalability.

As companies grow, informal role structures create risk. Titles drift. Compensation becomes inconsistent. Promotion decisions feel subjective. A formal job architecture reduces these risks by introducing clarity and consistency.

Here’s why it matters.

3.1 Enables Fair and Structured Compensation

Compensation without structure leads to internal inequity.

Job architecture connects roles to clearly defined levels and salary bands. This creates alignment between responsibility, impact, and pay. It also:

- Reduces pay compression

- Supports merit-based increases

- Strengthens pay equity compliance

- Makes compensation planning more predictable

For finance leaders, structured architecture improves budgeting accuracy and reduces ad-hoc salary adjustments.

3.2 Clarifies Career Paths

Employees want visibility into growth.

Job architecture defines what progression looks like — whether vertical (promotion) or lateral (career mobility). Each level reflects increasing:

- Scope

- Complexity

- Decision-making authority

- Organizational impact

This transparency improves retention and reduces ambiguity around advancement.

3.3 Improves Workforce Planning

Workforce planning becomes more strategic when roles are structured.

With clear job families and levels, companies can:

- Identify skill gaps

- Plan succession pipelines

- Forecast hiring needs

- Model future headcount costs

Architecture turns talent planning from reactive to proactive.

3.4 Strengthens Performance Management

When levels are clearly defined, expectations are clearer.

Managers can evaluate employees based on consistent criteria tied to scope and impact. This reduces bias and improves performance calibration across teams.

Instead of evaluating performance based on personality or visibility, leaders assess contribution relative to level expectations.

In growing organizations, job architecture acts as the backbone of talent and compensation strategy. It ensures that growth is structured, equitable, and financially sustainable.

Great — moving into the structural core of the article.

4. Core Components of Job Architecture

A strong job architecture framework is built from several foundational elements. Each component defines how roles are grouped, leveled, and differentiated across the organization.

When these elements work together, they create consistency in titles, expectations, and compensation.

4.1 Job Families

A job family groups roles that perform similar types of work and require related skill sets.

Examples of common job families include:

- Engineering

- Sales

- Marketing

- Human Resources

- Finance

- Customer Success

Job families help organizations organize work by discipline rather than by reporting structure. This allows consistent leveling and pay alignment within functional areas.

For example, all engineering roles — regardless of team — may fall under one engineering job family with standardized levels.

4.2 Job Functions or Sub-Families

Within job families, companies often define sub-functions or specializations.

For example, within Engineering:

- Frontend Engineering

- Backend Engineering

- DevOps

- Data Engineering

This level of structure helps distinguish skill depth and specialization while maintaining consistency within the broader family.

Sub-families are especially important in larger organizations where roles become more specialized over time.

4.3 Job Levels

Job levels define seniority and scope.

Levels differentiate roles based on increasing:

- Complexity of work

- Autonomy

- Decision-making authority

- Organizational impact

- Leadership responsibility

A typical leveling structure may include:

- Level 1: Entry-Level / Associate

- Level 2: Intermediate

- Level 3: Senior

- Level 4: Lead or Staff

- Level 5+: Principal or Executive

Clear leveling ensures that titles are not inflated and promotions reflect meaningful increases in responsibility.

4.4 Role Scope and Accountability

Beyond titles, job architecture defines scope.

Scope includes:

- Size of projects managed

- Revenue or budget responsibility

- Strategic vs operational impact

- Influence across teams

Two employees may share a title, but scope definitions clarify expectations and performance standards.

4.5 Competencies

Competencies describe the skills and behaviors required at each level.

These typically include:

- Technical competencies (role-specific expertise)

- Behavioral competencies (communication, collaboration)

- Leadership competencies (strategic thinking, people management)

Defining competencies by level helps standardize performance evaluation and promotion criteria.

4.6 Salary Bands

Salary bands connect job architecture to compensation strategy.

Each level is mapped to a defined pay range based on:

- Market data

- Internal equity

- Budget constraints

- Geographic considerations

Without salary bands, job architecture lacks financial discipline. With them, compensation decisions become structured, defensible, and scalable.

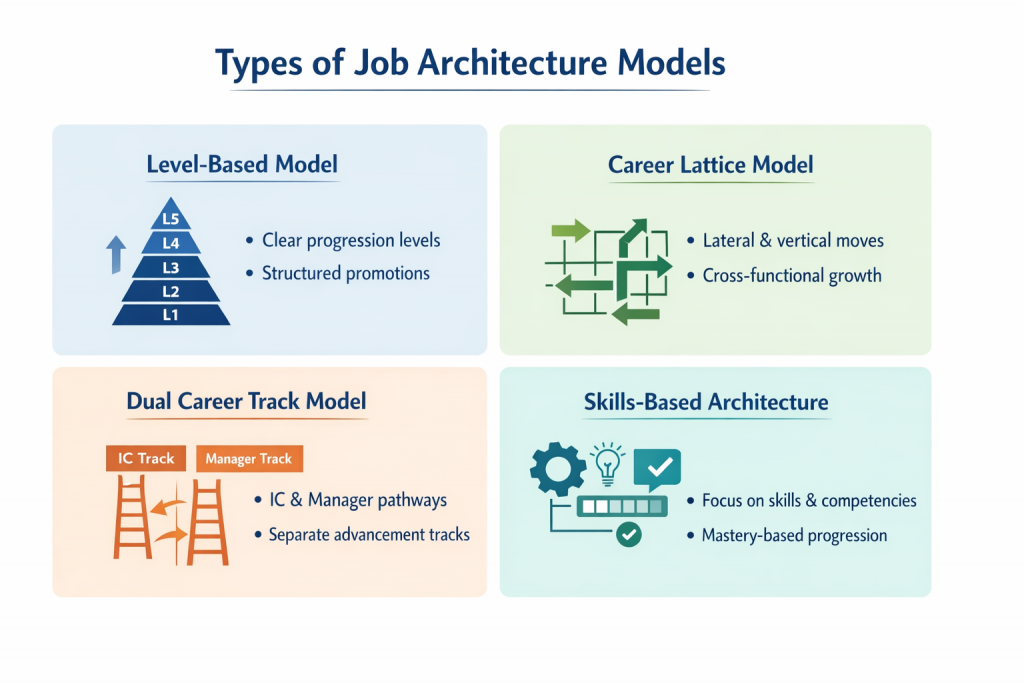

5. Types of Job Architecture Models

There is no single way to design job architecture. The right model depends on company size, growth stage, and strategic priorities.

Below are the most common approaches organizations use.

5.1 Level-Based Model

The level-based model is the most widely adopted structure.

Roles are organized into clearly defined levels within each job family. Progression is vertical, with increasing responsibility, complexity, and impact at each stage.

Example progression within Engineering:

- Engineer I

- Engineer II

- Senior Engineer

- Staff Engineer

- Principal Engineer

This model works well for companies that value clear hierarchy and structured promotions. It simplifies compensation planning and performance calibration.

However, if not designed carefully, it can encourage title inflation.

5.2 Career Lattice Model

The career lattice model allows both vertical and lateral movement.

Instead of viewing growth strictly as promotion, employees can move across functions, teams, or skill areas while maintaining level alignment.

For example:

- A Senior Analyst in Finance may transition to a Senior Analyst role in Strategy.

- A Marketing Manager may move into Product Marketing at the same level.

This model supports internal mobility and skill diversification, which can improve retention and workforce agility.

5.3 Dual Career Track Model

The dual career track model separates the Individual Contributor (IC) path from the Manager path.

Not all high performers want to manage people. This model ensures technical or specialist roles can progress in seniority and compensation without requiring team management.

For example:

Individual Contributor Track:

- Senior Engineer

- Staff Engineer

- Principal Engineer

Manager Track:

- Engineering Manager

- Senior Engineering Manager

- Director of Engineering

Both tracks may align at similar compensation levels but differ in scope and leadership responsibilities.

5.4 Skills-Based Architecture

An emerging approach is skills-based architecture.

Instead of focusing primarily on titles and tenure, this model organizes roles around capabilities and skill depth. Progression depends on demonstrated mastery rather than years of experience.

This approach is common in organizations adopting agile workforce strategies or project-based work environments.

While flexible, it requires strong competency definitions and continuous skill assessment systems.

Choosing the right model depends on organizational maturity, culture, and long-term workforce strategy. Many companies combine elements from multiple models rather than adopting a single pure structure.

6. Job Architecture Examples (Practical Illustration)

Understanding job architecture conceptually is useful. Seeing it applied makes it clearer.

Below are simplified examples of how job architecture may be structured across different job families.

Example 1: Engineering Job Family

In a level-based architecture, engineering roles may be structured as follows:

| Level | Title | Scope of Responsibility | Example Salary Range (USD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| L1 | Software Engineer I | Executes defined tasks with guidance | $85,000–$105,000 |

| L2 | Software Engineer II | Works independently on projects | $105,000–$130,000 |

| L3 | Senior Software Engineer | Leads projects and mentors juniors | $130,000–$160,000 |

| L4 | Staff Engineer | Drives cross-team technical initiatives | $160,000–$190,000 |

| L5 | Principal Engineer | Org-wide technical strategy impact | $190,000–$230,000 |

Notice how progression reflects more than tenure. Each level increases in:

- Autonomy

- Project complexity

- Strategic influence

- Organizational impact

The salary bands align with this increased scope.

Example 2: Sales Job Family (IC + Manager Tracks)

Sales organizations often use a dual-track structure.

Individual Contributor Track

| Level | Title | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| L1 | Account Executive | Owns small-to-mid accounts |

| L2 | Senior Account Executive | Manages larger or complex accounts |

| L3 | Enterprise Account Executive | Handles strategic enterprise deals |

Manager Track

| Level | Title | Focus |

|---|---|---|

| L3 | Sales Manager | Manages a team of AEs |

| L4 | Senior Sales Manager | Oversees multiple teams |

| L5 | Director of Sales | Owns regional or segment strategy |

In this structure:

- A Senior Account Executive and a Sales Manager may sit at comparable levels.

- Compensation differs based on quota ownership versus people management responsibility.

- Progression does not require switching tracks unless desired.

Example 3: Finance Job Family

A finance architecture might look like:

- Financial Analyst

- Senior Financial Analyst

- Finance Manager

- Senior Finance Manager

- Director of Finance

Here, movement reflects increasing ownership over:

- Budget planning

- Forecasting complexity

- Cross-functional influence

- Strategic financial decision-making

These examples demonstrate how job architecture standardizes titles, expectations, and pay across the organization.

Without this structure, titles may vary widely while responsibilities overlap — creating confusion and inequity.

7. How to Build a Job Architecture Framework (Step-by-Step)

Building job architecture requires cross-functional alignment between HR, finance, and leadership. It is not just a documentation exercise. It is an organizational design decision.

Here is a structured approach.

Step 1: Audit Existing Roles

Start by assessing your current state.

- List all active roles and titles

- Identify overlapping responsibilities

- Review current compensation ranges

- Note inconsistencies in leveling

At this stage, patterns typically emerge — duplicate titles, unclear scope differences, or pay misalignment.

Step 2: Define Job Families

Group roles based on the type of work performed.

For example:

- Engineering

- Sales

- Marketing

- Finance

- HR

- Operations

Avoid organizing solely by reporting lines. Focus on functional alignment and skill similarity.

Step 3: Establish Clear Job Levels

Define consistent levels across the organization.

Levels should reflect increasing:

- Autonomy

- Complexity

- Decision-making authority

- Organizational impact

Document leveling criteria clearly. A Level 3 in one function should reflect comparable scope to a Level 3 in another function, even if the work differs.

Step 4: Define Role Scope and Expectations

For each level within each family, clarify:

- Core responsibilities

- Expected outcomes

- Leadership expectations

- Influence and accountability

This reduces ambiguity in promotions and performance reviews.

Step 5: Align Compensation Bands

Map each level to a defined salary range.

Use:

- Market benchmarking data

- Internal equity analysis

- Budget planning constraints

- Geographic adjustments where relevant

Compensation alignment ensures the architecture translates into financial structure, not just titles.

Step 6: Validate Across Leadership

Before finalizing, review the framework with:

- Functional leaders

- Finance stakeholders

- Executive leadership

Pressure-test for edge cases and inconsistencies. Adjust where necessary.

Step 7: Communicate Transparently

Implementation success depends on communication.

Explain:

- How levels are defined

- How promotions are evaluated

- How compensation bands work

- What changes employees can expect

Transparency builds trust and reduces resistance.

A well-implemented job architecture becomes the foundation for structured growth. But poorly executed frameworks can create confusion or rigidity.

That’s why governance and periodic review are essential.

Great — this section adds realism and authority.

8. Common Challenges in Implementing Job Architecture

While job architecture brings structure and clarity, implementation is rarely frictionless. Organizations often encounter resistance, complexity, and unintended consequences if the framework is not carefully designed.

Here are the most common challenges.

Role Overlaps and Legacy Titles

In growing companies, roles evolve organically. Responsibilities shift without formal reclassification.

When building architecture, you may discover:

- Multiple employees with the same title but different scope

- Different titles for similar work

- Senior titles assigned without senior-level impact

Rationalizing these inconsistencies can be sensitive and politically complex.

Resistance from Managers

Managers may fear losing flexibility in hiring or promotions.

A structured framework limits discretionary title changes and ad-hoc pay decisions. Without proper alignment, leaders may view architecture as bureaucracy rather than enablement.

Early involvement and education are critical.

Pay Inequities Surface

When roles are formally leveled, compensation gaps often become visible.

Some employees may fall below the appropriate band. Others may be above it.

Correcting inequities requires budget planning and, in some cases, phased adjustments.

Overengineering the Framework

Some organizations attempt to create overly detailed systems with too many levels, excessive competencies, or rigid classifications.

This leads to:

- Administrative burden

- Slow decision-making

- Confusion among employees

A job architecture should be structured but practical.

Lack of Ongoing Governance

Job architecture is not a one-time project.

Without regular review:

- New roles may not fit cleanly into the framework

- Market compensation shifts may misalign salary bands

- Titles may drift again over time

Establishing governance processes ensures the framework evolves alongside the business.

Despite these challenges, the long-term benefits outweigh the implementation complexity. The key is balancing structure with flexibility.

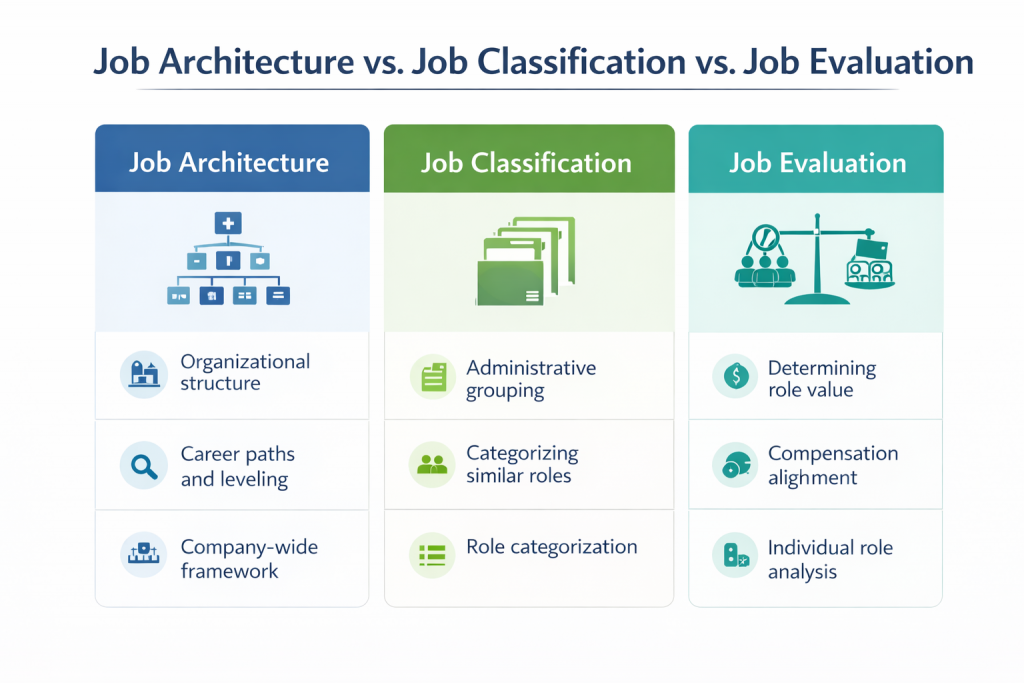

9. Job Architecture vs. Job Classification vs. Job Evaluation

These terms are often used interchangeably, but they serve different purposes within workforce and compensation strategy.

Understanding the distinctions prevents confusion during implementation.

Job Architecture

Job architecture is the overarching framework that organizes roles across the organization.

It defines:

- Job families

- Levels

- Career paths

- Role scope

- Alignment to salary bands

It provides structure and consistency across functions.

Job Classification

Job classification groups roles into predefined categories, often for administrative or compliance purposes.

It is commonly used in:

- Government organizations

- Unionized environments

- Large enterprises with standardized pay grades

Classification focuses on grouping similar jobs together, but it does not always define progression pathways or competency expectations in detail.

Job Evaluation

Job evaluation determines the relative value of a role within an organization.

It answers the question:

How valuable is this role compared to others?

Organizations use formal methods such as:

- Point-factor systems

- Market pricing

- Internal benchmarking

Job evaluation typically informs compensation decisions and salary band placement.

Comparison Table

| Aspect | Job Architecture | Job Classification | Job Evaluation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Purpose | Organizational structure | Administrative grouping | Determining role value |

| Focus | Career paths and leveling | Categorizing similar roles | Compensation alignment |

| Scope | Company-wide framework | Role categorization | Individual role analysis |

| Output | Levels, families, salary bands | Job categories or grades | Pay positioning data |

In simple terms:

- Job architecture builds the system.

- Job classification groups roles within it.

- Job evaluation determines how roles are valued and paid.

Together, they create a structured, defensible compensation and career framework.

Perfect — let’s close out the strategic guidance.

10. When Should a Company Implement Job Architecture?

Not every company needs formal job architecture from day one. In early-stage startups, flexibility often matters more than structure.

However, as organizations scale, the absence of architecture begins to create risk.

Here are key inflection points when implementation becomes necessary.

Rapid Headcount Growth

If your organization is hiring quickly, informal leveling breaks down.

New hires may negotiate titles and compensation inconsistently. Over time, this creates pay compression, title inflation, and internal equity concerns.

A defined architecture ensures consistency as hiring accelerates.

Promotion Inconsistencies

If promotions feel subjective or unclear, architecture can provide guardrails.

Employees should understand:

- What qualifies them for the next level

- How impact is measured

- What scope differentiates seniority

When these answers are unclear, engagement and retention suffer.

Compensation Restructuring

If you are:

- Introducing salary bands

- Conducting market benchmarking

- Addressing pay equity

- Preparing for merit cycles

You need a structured framework to align compensation decisions.

Post-Funding or Pre-IPO Stage

Companies entering later growth stages — such as post-Series A/B or preparing for IPO — require stronger governance.

Investors and boards expect:

- Compensation discipline

- Workforce cost predictability

- Structured career frameworks

Job architecture supports this operational maturity.

Organizational Complexity Increases

As teams expand and specializations deepen, role overlap becomes common.

When multiple employees perform similar work with different titles or pay ranges, architecture restores alignment.

In short, job architecture becomes essential when scale introduces complexity.

The earlier it is implemented thoughtfully, the easier it is to maintain equity, transparency, and financial discipline over time.

11. Conclusion

Job architecture is not just an HR framework. It is a strategic foundation for organizational clarity, compensation fairness, and scalable growth.

Without structure, companies risk title inflation, pay inequities, unclear career paths, and reactive workforce planning. As complexity increases, these issues compound.

A well-designed job architecture provides:

- Clear role definitions

- Transparent progression pathways

- Structured salary alignment

- Improved workforce forecasting

- Consistent performance standards

It connects talent strategy with financial discipline. It aligns HR and finance around shared principles of equity, accountability, and sustainability.

Most importantly, it creates trust.

Employees understand how growth works. Managers make consistent decisions. Leadership gains visibility into organizational structure and cost impact.

As companies scale, job architecture shifts from optional to essential. The organizations that invest in it early build stronger foundations for long-term success.